|

| Penguin Classics UK edition, 1975 |

'Ah, my dear friend, the way you express yourself!' Bazarov exclaimed. 'You see what I'm doing: there happened to be an empty space in my trunk, and I'm stuffing it with hay; it's the same with the trunk which is our life: we fill it with anything that comes to hand rather than leave a void. Don't be offended, please; you remember, no doubt, the opinion I have always held of Katerina Sergeyevna. Some young ladies have the reputation of being intelligent because they can sigh cleverly; but your young lady can hold her own, and do it so well that she'll take you in hand also –– well, and that's how it should be.' He slammed the lid of the trunk and got up from the floor. 'And now, in parting, let me repeat… because there is no point deceiving ourselves –– we are parting for good, and you know that yourself… you have acted sensibly: you were not made for our bitter, harsh, lonely existence. There's no audacity in you, no venom: you've the fire and energy of youth but that's not enough for our business. Your sort, the gentry, can never go farther than well-bred resignation or well-bred indignation, and that's futile. The likes of you, for instance, won't stand up and fight –– and yet you think yourselves fine fellows –– but we insist on fighting. Yes, that's the trouble! Our dust would corrode your eyes, our mud would sully you, but in actual fact you aren't up to our level yet, you unconsciously admire yourself, you enjoy finding fault with yourself; but we've had enough of all that –– give us fresh victims! We must smash people! You are a nice lad; but you're too soft, a good little liberal gentleman –– eh volla-too*, as my father would say.'

The Novel: The 'angry young man' has become such a stock figure in Western literature, beginning with Shakespeare's Hamlet and persisting into the modern era with characters like JD Salinger's Holden Caulfield (The Catcher in the Rye, 1951), John Osborne's Jimmy Porter (Look Back In Anger, 1956) and Chuck Palahniuk's Tyler Durden (Fight Club, 1996), that it can be easy to forget what a powerful impact he has had on the reading and playgoing public and, in a far less direct sense, on society as a whole. Every generation seems to require and invent its own version of this character –– the lone embittered rebel who yearns to destroy the prevailing social order and establish a new society where ideas like honesty, equality and compassion will rule the day, replacing the ubiquitous hypocrisies, lies and compromises which, in democracies and dictatorships alike, so frequently combine to define the nebulous concept of 'government.'

But the 'angry young man' has not only been a popular figure in the West. He was equally popular in nineteenth century Russia, a vast feudal nation ruled by a tyrannical Czar who believed, as had his ancestors for centuries before him, that the only way to prevent revolution was to ruthlessly crush anyone who dared to express the slightest desire for social, political or economic improvement. It was a time of extremists, of Nihilists and Anarchists, of cold-blooded revolutionaries determined to drag their virtually medieval nation –– where an aristocrat's wealth was literally measured by the number of 'souls' (ie. serfs, another word for peasants) he owned –– into alignment with the more 'civilized beliefs' and 'scientific practices' of the West, by persuasion, agitation and acts of indiscriminate violence when these proved necessary. On the other side stood the conservatives and moderates, men to whom the idea of reform was abhorrent because, to their fretful minds, it violated the natural order of things and challenged their right to continue leading the graciously indolent lives they led on their vast, poorly-run estates courtesy of the unremitting labour of their serfs. It is the conflict between these 'old' and 'new' orders, between the conservative patriarchs and their radicalized offspring, which serves as the background to Ivan Turgenev's 1861 masterpiece Fathers and Sons –– a novel many critics believe to be the greatest Russian novel ever written.

The story opens with Nikolai Petrovich Kirsanov, a middle-aged landowner and unsuccessful farmer, impatiently awaiting the homecoming of his son Arkady and his son's friend and mentor, the unsentimental medical student Yevgeny Vassilyich Bazarov, from the university in St Petersburg. Arkady has recently graduated from this institution and his return to the family estate has been eagerly anticipated by his father and his Uncle Pavel for several anxious months. But the arrival of Arkady and his guest, who soon reveals himself to be a Nihilist and an outspoken opponent of everything Nikolai Petrovich and the ultra-conservative Pavel value and respect, only serves to widen the gulf that has opened between father and son since the latter's previous visit to the family home. Although Nikolai Petrovich and Arkady remain on friendly, even affectionate terms with each other, the former feels he is now being replaced in his son's affections by Bazarov –– a man of strong, forcefully expressed opinions whom the easily swayed, eager to please graduate clearly idolizes.

Although Bazarov prides himself on being a Nihilist, even Nikolai Petrovich can admit that this does not automatically reduce his rival to the level of a completely untrustworthy or despicable figure. His son's hero is intelligent, articulate and certainly has something of the common touch about him, making him a favourite of Nikolai Petrovich's recently freed (if still impoverished) serfs and of his pretty young de facto wife Fenichka, mother of his 'other' infant son Mitya. (Arkady's mother has been dead for twelve years by this time.) Bazarov believes in science, reform and progress –– all the things, in short, that a so-called 'enlightened' Russian nobleman should have faith in but which, in the case of Nikolai Petrovich and the aloof and disappointed Pavel, spell the beginning of the end of the leisurely if sterile life they have lived together since choosing to turn their backs on progress and bury themselves in the country.

The young men manage to amuse themselves for a fortnight on the Kirsanov estate –– eating, walking, hunting, gathering specimens of flora and fauna and, in Bazarov's case, attending to the various ailments of its few remaining serfs. A sort of inter-generational truce prevails until Bazarov quarrels with Pavel at dinner one night, accusing the older man of being an out of touch sentimentalist who, along with all his kind, remains woefully ignorant of what Russia and its suffering people require to become truly free and satisfied. Pavel is outraged by these claims, but Bazarov is unmoved by his arguments, just as he is by what he curtly dismisses as being Pavel's futile, self-justifying theorizing. "Your vaunted sense of your own dignity has let you down," Bazarov sneeringly informs the older man. "I shall be prepared to agree with you… when you can show me a single institution of contemporary life, private or public, which does not call for absolute and ruthless repudiation." After this, he and Arkady bid farewell to the Kirsanov estate, leaving Nikolai Petrovich and his brother to lament over everything they and their class have been accused of condoning by this misanthropic member of the younger generation. Grateful to be free again, the young men travel on to a nearby town where they are warmly received by Nikolai Petrovich's friend Kolyazin, the district's progressive-minded but ineffectual (and thoroughly despotic) Governor. From here it is their intention to travel next to the home of Bazarov's parents, cash-strapped landowners who live on a much smaller estate located some sixty miles away.

Life as the guest of Kolyazin proves no more appealing to Bazarov than life as the guest of Arkady's kindhearted if unimaginative father had been. To relieve the monotony, he allows Arkady to drag him to the home of Madame Kukshin, a so-called 'advanced woman' who proceeds to bore him stiff with her talk of women's rights and her reverence for the writings of several well-meaning but politically irrelevant philosophers. She does, however, invite him and his young protégé to a ball, where she introduces them to a beautiful widowed aristocrat named Anna Sergeyevna Odintsov –– a woman, rumour has it, who obtained her fortune by cynically seducing and marrying her much older, now deceased husband. Like her more garrulous acquaintance Madame Kukshin, Anna Sergeyevna finds herself both attracted to and repelled by the outspoken Bazarov, whose reputation for radicalism has preceded him even into this quiet rural corner of Russia. Nevertheless, she invites him and Arkady to stay with her at her estate before they travel on to the infinitely more humble home of Bazarov's parents. The young men are curious about Anna Sergeyevna and happily accept her invitation, arriving at her estate to find themselves greeted by a pair of footmen in livery in the grand if laughably antiquated style of Catherine the Great. Their hostess appears half an hour later and introduces them to her shy but pretty younger sister Katerina, known to everyone as Katya, and to the cranky, doddery old aunt who shares their large, efficiently-run home with them.

|

| Signet Classics US edition |

Prolonged exposure to such a beautiful if emotionally distant woman soon sees Arkady and Bazarov fall madly in love with her –– the former in a calf-eyed, silently adoring fashion and the latter in a way which poses a direct threat to his firmly-held convictions about life and the despised concept of 'romance' on the most fundamental levels. Bazarov finds himself resenting Anna Sergeyevna for making him so conscious of her loveliness, for distracting him from what he insists is his one 'true' vocation. 'Suddenly he would imagine those arms that were so chaste one day twining themselves round his neck, those proud lips responding to his kisses, those intelligent eyes gazing lovingly –– yes, lovingly! –– into his own; and his head would swirl and for a moment he would be lost in reverie, till indignation boiled up in him again. He caught himself indulging in all sorts of "shameful" thoughts, as though a devil were mocking at him. At times it seemed as though a change were taking place in Madame Odintsov too, that there were signs of something special in the expression of her face, that perhaps… But at that point he would generally stamp his feet or grind his teeth and shake his fist at himself.'

Everything seems hopeless until Anna Sergeyevna invites Bazarov to visit her alone in her room one morning, ostensibly for the purpose of discussing a scientific text he had recommended that she read. Granted this unforeseen opportunity, the besotted medical student takes matters into his own hands and candidly declares his love for her, only to find his hostess unprepared, even flabbergasted, to be the object of such a passionately expressed romantic declaration. Neither party is left satisfied by the conversation and Bazarov, now feeling tormented and humiliated in addition to unsatisfied, resumes his interrupted journey to the home of his adoring parents, who have been expecting him all this time without realizing what has detained him on the Odintsov estate for so long. Arkady, confused by his own recent discovery that it is the shy, piano-playing Katya, not their world-weary hostess, whom he actually adores, also decides to leave, intending to return to the Kirsanov estate until he changes his mind at the last minute and decides to accompany Bazarov to his parents' house after all.

Arkady finds his friend much changed during the journey to the obscure and rather forlorn little village the Bazarov family calls home. Although Bazarov himself has lost none of his cynicism, he now seems exhausted and disappointed, a sufferer from the very 'romanticism' he has, in the past, so vehemently repudiated. Naturally, Bazarov's aging parents are overjoyed to see their son. Not having laid eyes on him for three years, his mother cannot stop showering him with kisses, alternating these embarrassing displays of affection with promises to dash off to the kitchen and make him something nice to eat the moment he should find himself feeling the slightest bit peckish. Bazarov's father, an ex-Army surgeon named Vassily Ivanych (who served in the same regiment as Arkady's paternal grandfather during the Napoleonic wars), behaves in the same adoring fashion, the result of which is to embarrass and irritate his son to the point where the young man is forced to extract a promise from Vassily Ivanych that both he and his mother will strive to 'control themselves' for as long as he and Arkady remain their guests.

Bazarov's visit, however, proves to be of much shorter duration than originally anticipated. He soon grows restless in such depressingly familiar surroundings and declares his intention to depart again for the Kirsanov estate, where he hopes to rededicate himself to his long-suspended scientific and medical studies in undisturbed seclusion. He and Arkady leave the following day, travelling only as far as the first town before Bazarov decides to take a detour that will permit them to pay an unexpected call on Anna Sergeyevna. They return to her estate to find their hostess looking listless and distracted, full of apologies for her failure to behave as graciously towards them as a woman of her class is expected to behave. The friends soon bid her farewell again, her invitation to revisit her estate when she is in a brighter frame of mind still ringing in their ears as their carriage rolls away.

Life in the home of Arkady's father soon re-assumes its former predictable routine. Bazarov spends his days dissecting plants and animals and arguing politics and other contentious issues with the easily angered Pavel, while Arkady divides his time between mooning over Katya and discussing the estate's future with Nikolai Petrovich –– someone, it has now become obvious, who is aging rapidly and will soon be incapable of managing his land without the assistance of his son. Aware that the uneducated but very pretty Fenichka finds him both dangerous and attractive, Bazarov attempts to overcome his unreturned feelings for Anna Sergeyevna by clandestinely kissing the girl in the estate's seldom visited lilac arbour early one morning. Unfortunately, this scene is witnessed by Pavel, who later that day challenges Bazarov to a duel in order to defend what he feels to be the shamelessly besmirched honour of his brother. Bazarov is more amused than frightened by the prospect of having to fight a pistol duel with Pavel and gamely accepts the older man's challenge, only to find himself being missed when it finally takes place, making it necessary that he wound Pavel in the thigh with his own unfired pistol in order that 'honour' should be satisfied.

The bullet wound is not serious and Pavel spends the next few weeks in bed recuperating from it, granting him the opportunity to speak privately to Fenichka about what has happened and ascertain if it is Bazarov or his forgiving if rather dimwitted brother whom the girl truly loves. After Fenichka declares her undying love for Nikolai Petrovich, Pavel recommends that his brother break with tradition and marry her immediately –– something Nikolai Petrovich has secretly longed to do for years to legitimize his 'other' son and repay Fenichka for the years of pleasure and loyalty she has so unstintingly given him.

Bazarov, in the meantime, has left the Kirsanov estate and returned alone to the home of his parents –– an event which allows the lovestruck Arkady to cease thinking of himself as his friend's protégé and at last take the steps required to become his own man. Arkady soon pays another solo visit to the Odintsov estate, where he proposes to Katya, much to the delight of his father and, eventually, of Anna Sergeyevna, whose feelings for the absent Bazarov remain mixed to say the least. Although she realizes that she loves Bazarov, Anna Sergeyevna remains too afraid of him –– and of the personal and social challenges he personifies for those of her class –– to confess her feelings or make anything more of their relationship. This, she feels, is a moot point anyway, as Bazarov himself made it abundantly clear, at the time of their last meeting, that he had no intention of making a fool of himself again by making further efforts to pursue her.

Everyone seems to settle into their assigned roles until word reaches Anna Sergeyevna that Bazarov, who had been treating one of the local peasants for typhus, has become fatally infected with the disease and is being nursed in his final illness by his broken-hearted parents. Bazarov begs to see her one last time before his death and she kindly agrees to visit him, arriving with an eminent German physician who immediately confirms the patient's own diagnosis that his case is a hopeless one. The dying man confesses to Anna Sergeyevna that he has never ceased to love her but that his love for her is useless to both of them, something she should make herself forget as quickly as possible. "Love is a form," he tells her, "and my particular form is already disintegrating. Better let me say –– how lovely you are!… Live long, that's best of all, and make the most of it while there's still time." He dies soon afterwards, the imprint of his beloved's lips still damp on his feverish brow.

Many changes occur in the lives of Anna Sergeyevna and her friends during the ensuing months. Winter finds Katya happily married to Arkady, whose father has been granted his fondest wish and is now just as happily married to Fenichka. Pavel, fully recovered from his leg wound, has left the family estate and retired to the German city of Dresden, where he plans to live out the remainder of his days in genteel if exceedingly dull seclusion, a barely living relic of a vanished era whom his fellow Russian emigrés consider to be a perfect gentleman if something of a long-winded, petty-minded bore. Anna Sergeyevna has also remarried, her new husband a man considered to be one of the future leaders of Russia by his friends, an up and coming lawyer who is 'quite young still, kindhearted and cold as ice.' It is only Bazarov's parents whose lives have taken a turn for the worse since the untimely demise of their son. Deprived of their darling Yevgeny, they spend their days lamenting his loss and tending to his grave in the tiny, otherwise neglected village cemetery in which he is buried, their adoration of him –– despite his passion, his cynicism, his honest if rebellious heart –– as unwavering as ever.

|

| Russian edition, date unspecified |

Fathers and Sons was a novel that stirred considerable controversy, if not outrage, in its day, with conservatives condemning Turgenev for glamorizing Nihilism in what they saw as being his overly worshipful portrayal of Bazarov while the radicals took him to task for not going far enough in condemning Czarist oppression and the socially destructive impact it continued to have upon their countrymen. Turgenev himself became a vilified figure, distrusted and attacked by critics on both sides of politics because –– unlike his more fiery contemporaries Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky –– he refused to view his work as propaganda, seeking only to reveal the situation in Russia as it actually was in all its seething, violent and often contradictory complexity. The task of the novelist, as Turgenev saw it, was not to deliver sermons about what were the 'right' and 'wrong' ways to fix Russia's many grievous social problems but, rather, to show how these problems influenced the lives and emotions of ordinary people, problems that would not begin to be addressed –– and then only after several more decades of unrelenting oppression and bitter political in-fighting –– until the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917 altered the political landscape of his homeland forever.

Bazarov, who for most readers remains the book's most compelling character, has frequently been described as 'the first Bolshevik' –– a description that, while accurate in one sense, ignores the crucial role that emotion plays in his story and what his misguided attempts to deny and defy it ultimately cost him. The scornful medical student is no bloodthirsty revolutionary, no ranting demagogue preaching Nihilism for its own sake. Rather, he's a deeply divided human torn between his sincere desire to see significant social change occur –– someone who freely acknowledges the sacrifices that such change will require of men like him in personal terms –– and his equally strong desire to lead a productive and contented life that does not exclude friendship, marriage to a woman he loves and, in time, a family of his own. I suspect that it was Bazarov's all too potent humanity, rather than what he and his 'type' represented and symbolized in socio-political terms, that raised the ire of Turgenev's detractors, causing them to stop and consider the fact that people, not the ideas or the slogans they choose to shout in support of them, are what endure and finally matter in the end. They clamoured for a one-dimensional black and white sketch and instead Turgenev gave them a meticulously detailed colour portrait, devastatingly realistic in its depiction of a dysfunctional society and of everything that, in the very different world of pre-Soviet Russia, so tragically defined it.

|

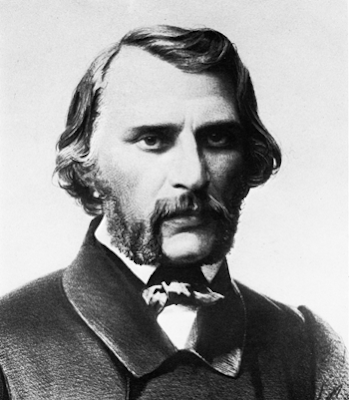

| IVAN TURGENEV, c 1860 |

The Writer: 'He felt and understood the opposite sides of life,' Henry James once wrote of his friend and fellow novelist Ivan Turgenev, 'our Anglo-Saxon, Protestant, moralistic conventional standards were far away from him… half the charm of conversation with him was that one breathed an air in which cant phrases… simply sounded ridiculous.' What to James's finely tuned ear sounded like virtues –– Turgenev's reticence and skepticism, his lifelong unwillingness to take sides, to pass binding judgements on people and issues that would subsequently have to be adhered to no matter what –– struck others as being proof of his procrastinating nature and lack of moral fibre, a betrayal not only of himself but also of the ongoing struggle to free Russia from its long unhappy history of Czarist oppression. Another friend, the poet Jacob Polonsky, writing to a reactionary minister two years prior to Turgenev's death in 1883, unflatteringly described the novelist as being 'kind and soft as wax… feminine… without character.' These conflicting views of Turgenev are and remain, even today, entirely typical. No one, it seems, can quite decide if he is somebody they should celebrate or deride, a writer whose work, while undeniably great, deserves to be praised for its candour or criticized for its creator's failure to take a fully committed political and social stance in what were turbulent and exceedingly dangerous times.

Turgenev's ambivalence –– or what some, friend and foe alike, chose to condemn as his 'moral weakness' –– can perhaps be best understood by examining the circumstances of his birth and childhood. The writer's father was a cavalry officer who, legend has it, was physically prevented from leaving the estate of his future bride-to-be so he would literally have no choice but to stay where he was and marry her. Colonel Turgenev was, by all accounts, a handsome and charming man who enjoyed the sexual favours of literally dozens of women –– qualities which made him doubly appealing to his allegedly 'ugly' bride, the heiress Varvara Petrovna Lutovinova, and also aided her transformation, in the words of critic Isaiah Berlin, into 'a strong-willed, hysterical, brutal, bitterly frustrated woman who loved her son, and broke his spirit.' Even before their father's death, which occurred when Ivan was sixteen, it was Varvara Petrovna who ruled the lives of himself and his brother just as she oversaw every aspect of life on their family estate, Spasskoye-Lutovinovo, located near the Ukrainian city of Oryol some 350 kilometres from Moscow.

As a child, Turgenev often saw his mother and other members of his family behave with unspeakable cruelty and even barbarity toward the serfs who worked their land for them. On one occasion, he allegedly watched in horrified silence as his maternal grandmother smothered a young peasant boy with a cushion so as not to have to listen to him groan after she had struck him to the ground in a fit of rage. The fact that his mother also beat himself and his brother regularly and, by all accounts, with great gusto (whether they had done anything to deserve being punished in this manner or not) was perhaps another reason for his later unwillingness to commit himself to radical or unpopular causes, no matter how noble or admirable their aims may have been. As a victim of what would nowadays be considered a textbook example of prolonged trauma-inducing child abuse, he probably learned at an early age that to protest or even express an opinion of his own was tantamount to inviting his mother to behave aggressively if not violently toward him.

Turgenev, his mother and his brother Nikolai left their estate in 1827 and moved to what, from that point onward, would be their new home in Moscow. After completing his schooling, Turgenev spent a year studying at that city's university before transferring, in 1834, to the University of St Petersburg where he remained for the next three years, reading Classics, Russian Literature and Philosophy. Although he published his first poems during his student years and had the chance to read History under professor (and novelist) Nikolai Gogol, he was dissatisfied with what he saw as being the inferior standard of education offered to men of his class in their native land and, in 1837, transferred again to the University of Berlin. He returned to Russia in 1840 to complete his Master's Degree and in 1841 began what was to be his brief career as a civil servant –– a career that ended for good with his resignation from the Ministry of the Interior in 1845 in order to pursue his 'gentlemanly' interests in literature, travel and hunting.

|

| PAULINE GARCIA VIARDOT, c 1870 |

His retirement from public life also allowed Turgenev to pursue another interest –– the Spanish-born opera singer and composer Pauline Garcia-Viardot whom he had first met in 1843. Turgenev soon followed Madame Garcia-Viardot and her husband and children to Paris, renting an apartment close to the family's lodgings so he could call on her each day. He would never again live very far from his heart's desire, accompanying her and her family on her concert tours of Europe and even sharing homes with them at various stages of what some believed to be a fully-fledged affair while others believed the relationship to be nothing more than an unconsummated (and strictly one-sided) infatuation. Although he never married himself, Turgenev did have several affairs with women who worked on his family's estate and even fathered an illegitimate child by one of them –– a girl named Pelageia who was later rechristened Paulinette and sent to Paris by her seamstress mother, at his request, to be raised alongside the Viardot offspring.

After 1862, when he left Russia for what proved to be the final time, Turgenev made his home permanently in Paris where his status as the 'family friend' of a celebrated opera singer gained him automatic entrée to the city's most fashionable salons and guaranteed his acceptance as one of their own by its most prestigious writers, publishers, artists and musicians. The appearance, in 1852, of Sketches from a Sportsman's Album –– a book of interrelated short stories which was one of the first literary works to offer readers a realistic depiction of the lives of Russian serfs –– had been greeted as a masterpiece both in Paris and its author's homeland, as had been his subsequent novels Rudin (1857), Home of the Gentry (1859) and On The Eve (1860). Turgenev's clear, balanced, meticulously exact style of writing earned him the respect and friendship of many of France's leading literary figures, including Gustave Flaubert, George Sand, Edmond Goncourt and Guy de Maupassant. His work also became increasingly popular in England and North America, with friends and admirers like Henry James doing everything within their power to ensure his works were translated and read shortly after they were published in French or –– less and less frequently as time went on –– in their native Russian.

It was, of course, in Russia that Turgenev received his greatest praise and faced his staunchest critics. The 1861 publication of Fathers and Sons proved, in many respects, to be the culmination of the Russian intelligentsia's love/hate relationship with his work and what he –– a wealthy landowner who had fled to the West rather than join the fight to improve the lives of the serfs whose miserable lot he 'pretended' to feel so moved by –– represented to it in political if not in literary terms. The book was attacked by radical critics for what they argued was its lack of 'seriousness' and many of the writer's own friends, including his own editor, accused him of having made the controversial figure of Bazarov too attractive and sympathetic, a sort of literary rallying point for the young with whom, they insisted, he had always striven too hard to curry favour. The controversy never really ended and Turgenev, despite frequent attempts to do so in letters sent to a wide variety of correspondents, never became fully comfortable with the energizing impact the character he had created came to have on Russian politics.

|

| IVAN TURGENEV, c 1875 |

Not even his two greatest contemporaries, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, could quite forgive Turgenev for what they separately dismissed as being his lack of backbone. The publication of his next novel Smoke (1867) led to an open quarrel with Dostoevsky in Baden-Baden, the German resort town in which both writers happened to be living at the time. Turgenev's relationship with Tolstoy, whom he was distantly related to and whom he had praised as a great writer long before Tolstoy had published any of his own masterpieces, was even less promising. Although they had been friends of a sort in their youth, with Turgenev taking Tolstoy to Paris and showing him the sights and visiting him several times on his family estate Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy once challenged him to a duel and described him as 'a bore' whose attempts to show his children how to dance the can-can were, as he famously confided to his diary, 'sad.' The two men did not speak for seventeen years but this did not prevent Turgenev, on his death-bed, from pleading with his kinsman to stop playing the role of a religious visionary and 'return to literature.'

Like its predecessor, Smoke also failed to win the approval of the Russian critics. This situation repeated itself with virtually everything Turgenev published between 1867 and his death from spinal cancer –– in the town of Bougival, just outside Paris, with Pauline Garcia-Viardot at his side –– on 3 September 1883. Although these later works –– the novels The Torrents of Spring (1877) and Virgin Soil (1879) and shorter, elegaic works including King Lear of the Steppes (1870) –– reveal a deepening of his artistic vision and, for their time, an uncannily perceptive interest in the role that memory and dreams play in defining human consciousness, they were generally not held to be the masterpieces they are now considered to be until the early years of the twentieth century, when new translations by Constance Garnett and others began to appear in England, North America and France. The success of these translations, and his growing reputation as the equal if not the literary superior of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, saw Turgenev become an important influence on a new generation of Modernist writers including Joseph Conrad, Virginia Woolf and the young Ernest Hemingway.

You might also enjoy:

Oblomov (1859) by IVAN CONCHAROV

Selected Poems 1909-1963 (1985) by ANNA AKHMATOVA

The Secret Agent: A Simple Tale (1907) by JOSEPH CONRAD

No comments:

Post a Comment