John Buscema: Michelangelo of Comics (2010) by BRIAN PECK

As a boy I was a voracious reader of many types of comics but my undisputed favourites were the superhero titles published by the Marvel Comics Group. Although a number of gifted artists worked for the company during its heyday in the 1960s and early 1970s — Gene Colan, Steve Ditko, Gil Kane, Jack Kirby, John Romita, the list is long and illustrious — I was particularly impressed by the dynamic, visually arresting work of John Buscema (1927–2002). Buscema's matchless knowledge of human anatomy, combined with his mastery of unusual perspective and unsurpassed ability to depict imaginary events in a naturalistic manner, made him one of the most widely imitated artists in the industry and one whose influence shows no signs of waning in the twenty-first century.

Like me, Brian Peck grew up reading and loving Marvel Comics and iconic Buscema-drawn characters like The Silver Surfer. 'One of the biggest regrets I have as a comic book reader and art collector,' he writes in his brief but affectionate 2010 biography of the artist, 'is that I never got to meet John Buscema, to tell him how much his art and stories meant to me, growing up. I hope this book will show in some small way, how "the man who hated comics" influenced many generations of readers, artists and the industry.' The book is a detailed chronological tribute to an artist who had, by his own admission, an ambivalent attitude toward the superhero genre and the 'unrealistic' characters he was required to draw to earn his living.

Peck traces Buscema's life from his birth in New York in 1927, through his formative years as a student at the city's School of Music and Art and his efforts to break into what was the relatively new World War Two-era comic book industry. He also discusses Buscema's abandonment of his cartooning career to pursue a new career as an advertising artist before returning to comics in 1966 at the request of Stan Lee, his former boss at what was known in the 1940s as Timely Comics before changing its name to Atlas and finally to Marvel prior to the superhero revival that began with the August 1962 publication of issue #15 of Amazing Fantasy and the debut appearance of an immediately popular new character called Spider-Man.

The transition from designing advertising layouts to drawing larger-than-life superheroes proved to be a challenging one for Buscema to negotiate. Lee reportedly hated the first stories his former employee penciled for Marvel, complaining that while Buscema showed a definite talent for illustration that did not automatically make him adept at creating the kind of tightly plotted layouts vital to the success of the modern comic book story. To solve this problem Lee gave Buscema several examples of Jack Kirby's work to take home and study, instructing the artist before he left his office that he must learn to 'Draw like that!'

By 1968, with his genre re-defining work on The Avengers impressing fans and colleagues alike, Buscema had become one of Marvel's top artists, creating characters and stories that would, within less than a decade, go on to achieve legendary status. He also set a new benchmark for the depiction of women in superhero titles, making female characters like The Wasp (AKA Janet Van Dyne) alluringly attractive without cheapening or belittling them in the process. While this hardly sounds radical today, it was a significant turning point in what was then a male-dominated and unapologetically sexist industry.

Splash Panel c 1977

© 2010 Marvel Characters Inc

Of course, comic books are a collaborative artform and Peck also takes the time to identify and praise the contributions made by Buscema's creative partners including the many talented artists who inked his work and Roy Thomas, the writer responsible for scripting much of it and introducing him to what would become his favourite character, Conan the Barbarian. 'Conan appealed to John,' Peck states, 'because he wasn't a superhero… Conan was real; he could be hurt. When it came to Conan, John dropped the superhero type of layouts for more realism.' The popularity of the character throughout the 1970s led to the creation of a larger format black-and-white magazine titled The Savage Sword of Conan that gave the A-list team of Thomas and Buscema the opportunity to produce longer stories featuring more adult-themed material. Buscema did much of his finest work for this magazine, his painstakingly detailed black and white drawings demonstrating that the time he'd spent as a boy studying the work of Renaissance artists Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci (and presumably Michelangelo as well) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art had not been wasted.

Peck is above all a passionate fan of the artist as is amply demonstrated by his detailed knowledge of every aspect of Buscema's work and his ability to write about it with both perception and intelligence. The book also includes an extensive bibliography and a meticulously curated list of the artist's entire published works, beginning with his earliest efforts for Timely Comics in 1948 and ending with Justice League of America: Barbarians his final unfinished assignment for DC Comics — the great rival to Marvel and a company he had rarely worked for over the years — in late 2001 prior to his death from stomach cancer the following January.

The book's only flaw, if it can be said to have one, is that none of Buscema's artwork is reproduced in color within its 167 pages. That said, the art is more than capable of standing on its own without that embellishment, welcome though it would have been.

John Buscema: Michelangelo of Comics is currently out of print.

Abrams Books

2015

Out of Line: The Art of Jules Feiffer (2015) by MARTHA FAY

The publication of this beautiful, copiously illustrated celebration of the work of North American cartoonist and all-round creative genius Jules Feiffer followed the appearance of his autobiography Backing Into Forward by five years and serves, in many ways, as a companion piece to that earlier, equally fascinating volume. While no one can tell Feiffer's story in quite the same humorously engaging way that Feiffer himself tells it, Martha Fay has done an excellent job of collating what is currently the most thorough visual survey of his work to appear in the upscale 'artbook' format.

Feiffer's story — for those who may be unfamiliar with his groundbreaking work for publications including The Village Voice and Playboy — is in many ways the story of cartooning itself in post-World War Two North America. Like John Buscema, Feiffer was a child of the 1920s who grew up devouring classic 'golden age' newspaper strips like Popeye and Flash Gordon and began trying to copy them from the moment he was old enough to hold a crayon. Again like Buscema, he found an entry level job in what was then a new and thriving comic book industry — in his case, as one of many assistants to Will Eisner, creator of The Spirit and the artist the industry's most prestigious award is today named in honor of — that led to him creating Clifford, his own newspaper strip, before he was drafted into the army (very much against his will) in 1951.

Becoming a soldier, Feiffer claimed, robbed him not only of his individuality but also of the power of speech. As he wrote in his autobiography: 'I'd have a thought in my head, I'd start to say something, but the words wouldn't follow the thought in my head… They were stealing my soul. They were turning me into a puddle — not a soldier, by any means.' Demoralizing as Feiffer's experiences of army life were, they did inspire his first long form cartoon story Munro, the tale of a five year old boy who's drafted by mistake but expected to loyally serve his country nonetheless. The story would not appear in print until 1959, by which time Feiffer had become internationally famous for the work he regularly published in the pages of The Village Voice.

It would be impossible to overestimate what a profound impact Feiffer's mid to late 1950s work had on his young, college educated, culturally aware, increasingly sophisticated audience. After trying and failing to launch a slew of syndicated daily newspaper strips, he began to utilize what he was experiencing in post-army New York life as material, giving his intensely personal angst-filled work an immediacy that, combined with his new, much looser drawing style and brilliantly witty dialogue, made it irresistibly appealing to a generation that, while financially better off than their parents' generation had ever dreamed of being, was struggling to deal with feelings of malaise, disenchantment and what was often a crippling if inexplicable sense of guilt.

First appearance of Bernard Mergendeiler

The Village Voice

13 November 1957

Feiffer's cartoons, featuring his hangdog alter-ego Bernard Mergendeiler and a host of other occasionally recurring characters, struck a chord with his readers just as the stand-up routines of comedians like Mort Sahl and Lenny Bruce were doing, poking fun at sexual relationships, careerism and the Establishment while expressing liberal political views that were very much at odds with those espoused by the nation's conservative-minded majority. In time Feiffer became much more than a cartoonist, going on to write several plays, a novel and the screenplay for the 1971 film Carnal Knowledge — a project that helped to make a major star of a young, still relatively unknown actor named Jack Nicholson and has long been considered an era-defining work of art in its own right.

Martha Fay does an excellent job of covering the many phases of Feiffer's career, including his Village Voice and Playboy years and his later triumphs as an author and illustrator of high quality children's literature. Her book is flawlessly designed and also features many of its subject's childhood drawings, something rarely seen in volumes of this kind. It is a treasure trove for Feiffer fanatics like myself and a handy reminder of an era when cartoon art was a central component of contemporary Western culture. It is also worth reading for the lively foreword penned by Mike Nichols, someone who first met Feiffer in 1958 and would go on to direct Carnal Knowledge along with several of his plays.

Out Of Line: The Art of Jules Feiffer remains in print and may be available from your local bookstore or preferred online retailer.

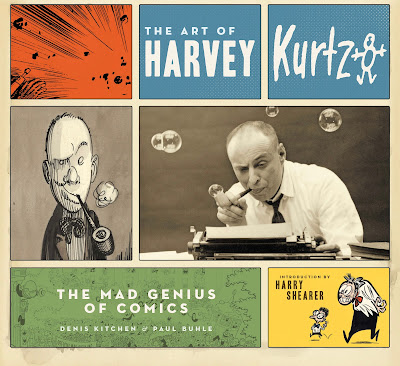

The Art of Harvey Kurtzman: The Mad Genius of Comics (2009) by DENIS KITCHEN and PAUL BUHLE

No North American cartoonist probably had a greater influence on his peers and the artists who followed him than Harvey Kurtzman (1924–1993). And when I say 'artists' I mean artists in the broadest possible sense of the term, as did the editors of The New York Times when they described him, not at all inaccurately, as 'One of the most important figures in post-war America.'

Kurtzman's work had just as great an impact on the worlds of cinema and animation as it had on the worlds of art and design despite the fact he never directly worked in the motion picture industry and worked only briefly as an animator. As award-winning comic artist Art Spiegelman states in his introduction to this long overdue celebration of his former mentor's life and many astonishing achievements, 'Kurtzman's MAD held a mirror up to American society, exposing the hypocrisies and distortions of mass media with jazzy grace and elegance. He's our first post-modern humorist, laying the groundwork for such contemporary humor and satire as Saturday Night Live, Monty Python and Naked Gun.'

Kurtzman, the middle son of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, was born in New York City in 1924 and, like his younger contemporary John Buscema, attended the city's vocational High School of Music and Art. He was drafted in 1943 and honorably discharged two years later, returning to New York to pick up where he had left off as assistant to visual artist and 'content creator for hire' Louis Ferstadt. Within months this led to a host of other assignments and, eventually, to him earning a precarious living as a freelancer for companies like Timely where, again like Buscema, he was supervised by its brash young editor Stan Lee.

Specializing in wacky humor strips like Hey Look!, Kurtzman developed an idiosyncratic, slightly surreal approach to sequential art that directly challenged the established conventions of what was generally considered to be a medium created for and marketed exclusively to children — skills that would prove invaluable when he began drafting and editing graphic horror stories for EC Publications in the early 1950s in a series of eye-popping titles that included Tales From the Crypt, The Haunt of Fear and Weird Fantasy.

Many of the stories and covers Kurtzman subsequently created for EC would go on to become legendary, with his original artwork selling for thousands of dollars after the new generation of 'underground comix' artists like Robert Crumb (creator of Fritz the Cat) and Gilbert Shelton (creator of The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers) confessed to being inspired by his work. Horror comics — a genre that Kurtzman himself is said to have disliked — went on to become the bestselling titles of the 1950s, closely followed by war and science fiction comics that he, with his genius for creating striking cover images and attention grabbing splash panels, was likewise instrumental in perfecting and popularizing.

Cover of MAD magazine #1

October-November 1952

Art and design by

HARVEY KURTZMAN

Kurtzman followed his virtually one-man re-invention of the horror, war and science fiction genres with an equally bold re-invention of the modern humor magazine. As Jules Feiffer was discovering, readers' tastes were changing and so were the subjects they were interested in reading about. The publication of Issue #24 of MAD magazine in July 1955 was a watershed moment in the history of the North American periodical industry, with EC ditching the traditional comic book format (at Kurtzman's urging) to present MAD as a slicker, larger format magazine of undeniably superior quality. Issue #24 of MAD proved so popular that it eventually had to be reprinted, a phenomenon unheard of in the industry at that time.

But trouble was brewing behind the scenes for companies like EC. The forces of conservatism, alarmed by the gore and violence they perceived to be an integral feature of post-war comics, were using their government connections to try to censor the entire industry. The negative publicity generated by this highly publicized censorship campaign affected EC's bottom line profits and eventually saw the increasingly popular MAD — a subversive magazine if ever there was one — sold off to the powerful American News Company conglomerate.

The controversy over censorship, along with his natural skepticism and love of truth, underpins all the outstanding satire that Kurtzman would go on to create and publish in the pages of MAD. Finally freed from the onerous task of personally drawing, writing and designing every new issue of the magazine, he was able to employ a talented team of writers and artists, notably Wallace Wood, to create hilarious parodies of what had previously been off-limits content like classic films, animated cartoons, syndicated comic strips and the new 'threatening' medium of television. (He even poked fun at the 1950s experiment with 3D films, creating a 3D comic strip that remains, to this day, the only truly successful print media example of this process.)

Despite his creative boldness, Kurtzman remained frustrated by the fact that the ultimate arbiter of what could and could not appear in the pages of MAD was its new publisher, William Gaines Jr. Frustrated by this ongoing lack of creative control, Kurtzman quit the magazine in 1956, ushering in a long period of work that Kitchen and Buhle describe as being 'perennially disappointing or catastrophic, marked with flashes of creative brilliance and opportunity that faded from sight soon enough.'

Kitchen and Buhle are the ideal authors to explore and comment on Kurtzman's enduring artistic legacy, with Kitchen having served as the artist's creative executor since his death as well as being a gifted cartoonist and pioneering editor and publisher in his own right. They're particularly good at unraveling Kurtzman's often complicated relationships with his various bosses and his equally complicated relationship with the world of commerce. (Unlike his close friend Will Eisner, creator of The Spirit, Kurtzman did not retain ownership of the vast majority of his work and was therefore unable to reap the financial rewards it should have brought him following his 're-discovery' by the underground in the late 1960s.)

Although he continued to create and edit a number of magazines throughout the 1960s — a list that includes Humbug and Help! among others — and was instrumental in launching the careers of Robert Crumb and future Monty Python member Terry Gilliam, Kurtzman was never adequately remunerated for his work even after his strip Little Annie Fanny, co-created with long time friend Will Elder, made its debut appearance in the pages of Playboy in 1965. (He assumed that he and Elder owned the copyright to the character without getting their ownership confirmed in writing by Hugh Hefner and his lawyers. The result was a 26 year run on a project that earned him thousands when, based on circulation alone, it should have earned him millions.) Although he made a good enough living to support himself and his family, he became increasingly reliant on Playboy as his primary source of income, sometimes to the detriment of the other projects he would pursue throughout the 1970s, 1980s and prior to his death, at the age of sixty-eight, in 1993.

This book is a loving and cleverly designed tribute to the influential genius of Harvey Kurtzman, featuring a range of accompanying illustrations that are as diverse as they are far-ranging, covering every aspect of his career in exactingly comprehensive detail. Kitchen and his co-author Buhle, an academic who specializes in studies of comic book art and other forms of popular culture, are to be applauded for producing what ranks as one of the most impressive overviews of the work of any North American artist, cartoon or otherwise, ever published. Like the work of its subject, the book is a classic of its kind that no self-respecting pop culture fan can afford to be without.

The Art of Harvey Kurtzman: The Mad Genius of Comics is currently out of print.

You might also enjoy:

No comments:

Post a Comment