There are virtuoso performers who have not found an identity. That thumbprint is missing. With Bing you knew right away who he was. And you knew that he knew. He really is the first American jazz singer in the white world. Bing was an enormous influence. You couldn't avoid him. He had a good beat. He was a jazz singer, he knew what jazz was, and could sing a lyric, say the words, and make you hear the notes. Bing could swing. When he sang, the tune swung, whatever it was.

Mention the name 'Bing Crosby' to most people and the first image that generally springs to mind is that of an avuncular, pipe-smoking sexagenarian crooning the festive Irving Berlin chestnut White Christmas over a lush if respectfully sedate accompaniment. Even today, more than four decades after his death on a Spanish golf course, Crosby still seems to epitomize the term easy listening –– pleasant, predictable, featuring nothing in his choice of material, arrangements or orchestrations which could conceivably be described as 'cutting edge' or in the least sense challenging.

But this was not always the case for the vocalist, actor, producer, entrepreneur and philanthropist born Harold Lillis Crosby Jr on 3 May 1903 in the Washington port city of Tacoma. There was another Crosby –– he earned the nickname Bingo, later shortened to Bing, from a neighbor thanks to his boyhood fondness for the comic strip Bingo From Bingville –– who, in the words of clarinet virtuoso and bandleader Artie Shaw, '… was the first hip white person born in the United States.' This Bing Crosby was a sonic pioneer, the artist who singlehandedly invented the art of modern popular singing and privately funded the development of the tape recorder, influencing scores of performers both black and white who were as enraptured as the general public so quickly became by his mellifluous baritone voice and relaxed but acutely precise phrasing.

Crosby was first introduced to music by his father Harry Crosby Sr, who brought home an Edison Talking Machine –– the round cylinder-playing precursor to the flat disc playing gramophone –– not long after the family moved from Tacoma to Spokane in 1906. In time this machine was replaced by a Victrola and a collection of 78rpm records featuring the music of Gilbert and Sullivan, Irish tenor John McCormack, Scottish music hall star Harry Lauder and the nation's newest singing sensation, a brash young Jewish vaudevillian named Al Jolson whose 1912 hit The Spaniard That Blighted My Life would go on to sell more than a million copies. Jolson's impact on the young Crosby was immediate and considerable. ' "I'm not an electrifying performer at all",' he would later tell an interviewer. ' "I just sing a few little songs. But this man [Jolson] could really galvanize an audience into a frenzy. He could really tear them apart." ' Crosby knew what he was talking about because he saw his idol perform live in the hit 1917 show Robinson Crusoe Jr while employed for the summer as a prop boy at The Auditorium, the most prestigious vaudeville theater in Spokane. Jolson's repertoire would serve as the template for Crosby's earliest recordings as lead vocalist for The Rhythm Boys, with highly romanticized 'Songs of the Old Southland' (nearly all of which were churned out by professional songwriters in New York City) like Magnolia remaining staples of his own extensive repertoire for the rest of his career.

But Crosby possessed qualities that Jolson, for all his energy and talent, could not realistically hope to equal –– a seemingly instinctual understanding of rhythm and swing, a genuine love of jazz and a gift for understated delivery that demonstrated his mastery of microphone technique at a time when the microphone itself was a new form of technology that could intimidate even the most seasoned performers both in and out of the recording studio.

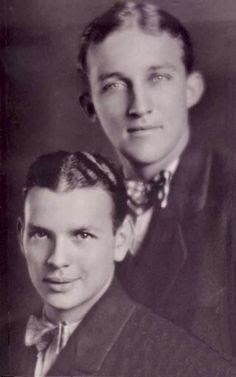

Crosby's career began in 1923 when he joined a band called the Musicaladers which had been formed by some Spokane high school students, one of whom was Native American pianist/manager Alton Rinker. Crosby was the band's entirely self-taught drummer and occasional featured vocalist and was soon earning enough from its performances at local dances to feel confident enough of his future to drop out of college in his senior year. Despite enjoying a modicum of success in Spokane, the band split up in the spring of 1925, prompting Crosby and Rinker to try their luck as a harmonizing duo, filling in between silent films at the city's newly converted Clemmer Theater –– an experience that would prove invaluable when, still determined to make it big in the music business, they relocated to Los Angeles in the fall.

Luckily, Rinker's older sister was Mildred Bailey –– an already established performer of the 'racy' jazz and blues music popular in the city's speakeasies as illegal gambling and/or drinking clubs were then known. (The Volstead Act, which prohibited the manufacture, sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages within the United States, had passed into law on 28 October 1919, giving the green light to organized crime to make millions by turning drinking into a 'sinful' and therefore desirable activity much favored by the young, including the perpetually thirsty and frequently intoxicated Mr Crosby.) Bailey was impressed by their act and immediately started making calls to try to find them work. She was also the person who introduced Crosby, with whom she would go on to forge a lasting and mutually appreciative friendship, to the recordings of black blues performers Bessie Smith and Ethel Waters and recommended that he listen to a young cornettist named Louis Armstrong who was currently recording for the OKeh label and playing up a storm each night in Chicago. Crosby, who was already a fan of white jazz acts like The Original Dixieland Jazz Band and The Wolverines, took her advice, finding a new source of inspiration in Armstrong's astonishing talent for both instrumental and spontaneous vocal improvisation. This was something he would soon learn to incorporate into his own, much smoother style of singing, using his voice to mimic instruments as he 'scatted' or improvised on melodies like a jazz musician. While it hardly seems earth shattering now, it was a completely new sound in the mid-1920s, paving the way for his successful emergence as a solo artist and influential cultural force throughout the following decade.

But in 1925 all of this still lay ahead of the twenty-two year old crooner from Washington state. His elder brother Everett was also living in Los Angeles at this time and it was he who allegedly got Bing and Rinker their first paying job at the Cafe Lafayette, a speakeasy whose house band was led by Harry Owens (future composer of Sweet Leilani, a faux Hawaiian song that would be a massive hit for you-know-who in 1937). The job didn't last long and, thanks to the persistence of Mildred Bailey, the pair soon auditioned for and were offered a place in a traveling vaudeville revue titled The Syncopation Idea. ('Syncopated music' was one of the early names for jazz, its use in the title of a revue confirming how popular the music had now become among mainstream white audiences.) They toured in this show for thirteen weeks, developing a small but loyal following among college students, and then joined Will Morrissey's Music Hall Revue, earning the same $75 per week they had earned while appearing in their first show. When the Morrissey revue closed, they joined another revue variously known as The Purple and Gold Revue, Bits of Broadway, Russian Revels and, after still more tinkering with its title and running order, Joy Week.

It was while they were appearing in Joy Week at the Metropolitan Theater in Los Angeles that they were handed a note from Paul Whiteman, the most popular bandleader in the country who was billed –– not at all accurately –– as 'the King of Jazz.' Impressed by their mixture of close harmony singing, comedic interludes and occasional use of exotic instruments like the kazoo, Whiteman offered them a featured spot with his band starting at a weekly salary of $150. They made their debut with his organization at the Tivoli Theater in Chicago on 6 December 1926, two months after secretly recording the song I've Got The Girl for their new boss's former saxophonist in a converted warehouse in Los Angeles. It was not an auspicious beginning to what would be Crosby's long and successful career behind the microphone. The song was second-rate at best and somehow recorded at the wrong speed, making him and the higher voiced Rinker sound like a pair of harmonizing chipmunks when it was played at the standard 78rpm speed. Thankfully, their names did not appear on the label of the Columbia release because, as employees of Whiteman, they were contracted to record exclusively for Victor, the same label which claimed exclusive rights to all of the bandleader's recordings.

The Rhythm Boys with Jack Fulton [vocals]

Recorded 23 November 1927

The opportunity to appear with the Whiteman Orchestra was equivalent to winning a million, pre-Depression dollars in showbusiness terms. Not only would Crosby and Rinker be performing nightly with the most popular band in the country, they would also be touring with some of the very best white jazz musicians currently active in North America. These included cornettist Bix Beiderbecke, guitarist Eddie Lang, trombonists Jimmy Dorsey and Jack Teagarden and saxophonists Frank Trumbauer and Tommy Dorsey, nearly all of whom would go on to have significant solo careers in both small group and big band jazz. Appearing in Chicago also allowed Crosby to visit the Sunset Cafe to hear and meet Louis Armstrong, of whom he was later to say, ' "I'm proud to acknowledge my debt to the Reverend Satchelmouth. He is the beginning and the end of music in America. And long may he reign." ' Armstrong returned the compliment in his 1930 recording of I'm Confessin' (That I Love You), consciously mimicking some of his white friend's vocal mannerisms in his own inimitable style. Crosby and Armstrong would go on to perform together many times on both radio and television and would even record a disappointing LP of Dixieland tunes in 1960 titled Bing and Satchmo following their much beloved duet Now You Has Jazz in the film High Society four years earlier.

The Rhythm Boys were an instant hit with audiences and also with Whiteman who negotiated a separate contract for them with Victor and sent them back into the studio in June with some of his best musicians, a group which included Crosby's hotel roommate (and third great musical influence) Bix Beiderbecke, violinist Matty Malneck and saxophonist Jimmy Dorsey. Their first recording featured a co-written Barris original, yet another catchy ode to the genteel 'old plantation' image of the antebellum south titled Mississippi Mud which established the pattern for virtually all their future recordings –– lots of percussive vocal effects, bantering wordplay and, as time progressed, the featuring of Crosby's smooth baritone with Barris and Rinker more often than not relegated to the roles of harmonizing sidemen. This, combined with Crosby's continuing musical education courtesy of Beiderbecke and other musicians attached to the Whiteman organization plus his own growing confidence as a performer, soon saw him being handed regular solo spots by Whiteman's arranger Bill Challis. By April 1928 his name was appearing beneath the bandleader's on record labels and in March 1929 he released his first side under his own name, a soulful number titled My Kinda Love on which he was accompanied only by piano, violin and guitar.

The music business was changing and tastes were changing with it, aided in part by the advent of talking pictures and the enthusiastic reception of early movie musicals like The Broadway Melody and The Hollywood Revue of 1929. The public's fondness for the brashness of Jolson (still modestly billing himself as 'The World's Greatest Entertainer') was replaced by a new craze for crooners like Rudy Vallee, Chick Bullock and Cliff 'Ukulele Ike' Edwards, making Crosby's shift to a full-time solo career a foregone conclusion. Although The Rhythm Boys survived as a group until 1930, it was as a solo artist that Crosby was to find his greatest success and establish himself as the pre-eminent white male vocalist in North America and, in time, throughout much of the Western world. Many of the songs he would record under his own name during the 1930s –– Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams, Just A Gigolo, Sweet and Lovely, How Deep is The Ocean? and I Surrender, Dear to name just a few –– would go on to become well-respected standards, performed not only by vocalists he directly influenced like Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and Perry Como but also by many important jazz artists including Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis and Sonny Rollins.

Crosby's growing presence on the cinema screen –– he had appeared in King of Jazz in 1930 as a member of the Rhythm Boys and would star in a series of comedic shorts for the Educational/Sennett company between 1931 and 1933 –– and on radio in his own nationally syndicated programs brought his music to even an wider audience and, for close to two decades, saw him consistently voted the number one male vocalist in the United States. While his recordings quickly became less directly jazz influenced, featuring elements of Tin Pan Alley, Latin, Hawaiian and Irish music, this didn't prevent him from appearing in the 1941 film Birth of the Blues, a fictionalized account of the early days of jazz, or from recording albums like Bing and The Dixieland Bands, featuring the band of his younger brother Bob Crosby, in 1951 or the outstanding Bing With A Beat featuring Bob Scobey's Frisco Jazz Band six years later. The jazz influence may have become submerged due to commercial considerations and the orchestrations written for him by his longtime arranger John Scott Trotter, but it was always there in his phrasing and in the way he made even the most banal material glide and swing.

For me, Crosby's greatest jazz performance will always be his 1932 recording of St Louis Blues with Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. While it wasn't his first performance with Ellington –– that was a version of Three Little Words he'd cut with the bandleader as a member of The Rhythm Boys in 1930 –– it was certainly his best, proving to anyone who doubts it that he had a feeling for jazz that was, given his race and upbringing, nothing short of remarkable. I've often wondered why he never recorded with Ellington again and what marvels may have been produced had they focused exclusively on interpreting the bandleader's own distinctively evocative compositions. Although Crosby would go on to do many great things before his death in 1977 –– including funding the development of the tape recorder for commercial use and revolutionizing the way radio programs and records were created, marketed and broadcast –– nothing ever quite equalled what he achieved as a young solo star in the third decade of the twentieth century where, as he always insisted, he just happened to be in the right place at the right time.

featuring

No comments:

Post a Comment