Thursday, 31 December 2020

Think About It 062: ELI PARISER

Thursday, 24 December 2020

The Write Advice 142: KATHERINE ANNE PORTER

Thursday, 17 December 2020

Delius As I Knew Him (1981 revised edition) by ERIC FENBY

|

| Faber and Faber Ltd revised UK edition, 1981 |

My friendship with Delius has confirmed in me that things of the spirit are of the first concern: that artistry plus technique –– not too much technique, however, but a little in hand –– are as essential in life as in the arts; that one should do in the arts rather than learn; that faults should be pointed out and corrected after the experience of doing, not explained beforehand; that the people who really count are those who discover new ways of making our lives more beautiful. Frederick Delius was such a man.

The Memoir: Musical genius is a rare quality in human beings, something the majority of us can only fantasize about possessing even if we're fortunate enough to be blessed with a well-tuned ear and a modicum of talent. Even rarer is the opportunity to gain regular unrestricted access to such genius and, rarer still, to dwell side by side with it, both observing and interacting with it on a daily basis. But this was precisely what a twenty-two year old self-taught musician named Eric Fenby was able to do after writing to Frederick Delius in May 1928 and offering the blind and paralysed composer his services as his live-in musical assistant or amanuensis.

Fenby's first contact with Delius was an earlier letter in which he had expressed his enthusiasm for the composer's majestic 1905 choral/orchestral work A Mass of Life. Never expecting to be answered, Fenby was shocked to receive a reply from Delius (dictated to his wife Jelka) a few weeks later, thanking him for his interest. Believing this must be no more than a polite gesture prompted by the fact that he and Delius were fellow Yorkshiremen –– the composer was born in Bradford in 1862 following his family's emigration from Germany, while Fenby himself had been raised in the seaside town of Scarborough after being born there in 1906 –– the young man found himself becoming obsessed with the notion of helping Delius finish the compositions he was unable to finish due to his chronically poor health. 'It chased me like some Hound of Heaven,' Fenby later confessed, 'and I hid from it under any and every excuse I could find; but it was always there, and in the end I could not sleep for it. Finally it conquered me, and, getting up in the middle of the night, I took pen and paper and wrote to Delius offering my help for three or four years.' In October, his offer gratefully accepted, the Scarborough lad was on his way to the small French village of Grez-sur-Loing which, excluding trips home to visit his parents and work as assistant to Delius's greatest champion the conductor Thomas Beecham, would more or less remain his home until 1933.

It was not, of course, all smooth sailing following Fenby's arrival in France. Neither he nor Delius had any conception of how they were going to work together and no way of predicting if their unusual partnership would yield acceptable results. In fact, Fenby's first attempt to take down Delius's musical dictation was little short of disastrous, with the composer later admitting to Jelka that '…[the] boy is no good… he cannot even take down a simple melody.' That Fenby was able to persevere and help his employer compose or complete at least ten major musical works –– including A Song of Summer, the Irmelin prelude and several chamber and vocal pieces –– is a testament both to his great love of Delius's music and his own iron-willed determination.

Delius, whose physical condition had been steadily deteriorating since he'd first been diagnosed with syphilis around 1901, was a demanding, cantankerous, highly opinionated man who ridiculed Fenby's staunch Catholicism and made several unsuccessful attempts to permanently rid his assistant of his religious convictions. Without the praise and encouragement Fenby received from the composer's uncomplaining wife, and Delius's own gestures of generosity such as presenting him with his own gold watch as a token of his appreciation, it's doubtful he would have lasted in Grez-sur-Loing for as long as he did or been capable of assisting Delius to achieve what he did in what is now regarded as being his last 'great' period of composition. While living in the Delius household allowed Fenby to meet and form friendships with some of the most prominent figures in English music –– a list which included the aforementioned conductor Thomas Beecham plus the composers Philip Heseltine, Balfour Gardiner, Edward Elgar and Percy Grainger –– it also took an immense physical and emotional toll on him, resulting in at least one nervous breakdown (which, in his characteristically self-effacing way, he never discusses in his memoir).

|

| JELKA and FREDERICK DELIUS, c 1932 |

The one flaw in Fenby's generally fine book is his own, sometimes awkwardly handled absence from its narrative. His very English reluctance to speak more directly and in greater depth about his own emotional state was probably something he saw as a self-protecting virtue, whereas the reader often wonders how he must have felt when such-and-such an incident occurred or Delius did or said this, that or the other to him. While he can be extremely candid about his employer's failings and equally quick to praise his virtues, he's careful not to delve too deeply into anything that might hint at controversy or cause discomfort to himself, his friends or his readers. The word 'syphilis,' for example, is mentioned only once and only in the notes he prepared for the revised 1981 edition of the book. (The original edition appeared in 1936, two years after the death of Delius.) Still, these are minor quibbles because Delius As I Knew Him remains a valuable record of a life lived uncompromisingly, written with skill and compassion by a man whose selfless generosity was entirely commendable. The book is equally valuable for the kind and sympathetic portrait it paints of Jelka Delius, in many ways the unsung hero of her husband's life whose support and understanding, both spiritual and financial, was what enabled him to become the artist he became and sustained him during his long slide toward a painful, humiliating and, in the end, much welcomed death.

|

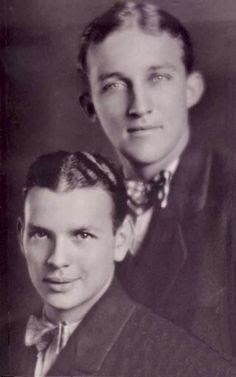

| ERIC FENBY and FREDERICK DELIUS, c 1930 |

Fenby was employed by Delius for six years between 1928 and 1934, after which he returned to England where he became assistant to the conductor Sir Thomas Beecham. In 1936 he returned to Yorkshire where he spent three months writing Delius As I Knew Him –– a cathartic task he pursued in total isolation so that his reminiscences could be recorded, he said, as accurately as possible. Following the book's publication later that year –– an event hailed by many as being the catalyst for a long overdue reappraisal of its subject's music –– he accepted an advisory role at the music publishing firm Boosey and Hawkes where he recommended works by the then little known Benjamin Britten and other young British composers including John Ireland and Arthur Benjamin. His friendship with hotelier Tom Laughton, brother of Scarborough-born actor Charles Laughton, led to an invitation from the latter to travel to Hollywood to compose the score for Jamaica Inn, a new Alfred Hitchcock film that Laughton was scheduled to appear in. Fenby's score was singled out for special praise by the critics and it's likely he would have go on to compose the score for Laughton's next film, the iconic The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939), had World War Two not intervened and called him back to England where he was immediately conscripted into the Royal Artillery. His stint as an artilleryman did not last long, however, once his superiors learned that such a gifted musician was spending his days '…painting white lines on roads.' In 1940 he was transferred to the Army Education Corps and spent the remainder of the war lecturing to the troops on musical subjects, composing military music and scores for army stage productions and training films, and conducting the Southern Command Symphony Orchestra.

Having by now abandoned his adopted Catholic faith, Fenby married vicar's daughter Rowena CT Marshall in 1944 and eventually became the father of a son named Roger and a daughter named Ruth. His return to civilian life in 1945 also saw him return to Yorkshire where, three years later, he founded and served as director of the Music Department of the North Riding Training College, a post he would retain until 1962. That year he was also appointed artistic director of the Delius Centenary Festival being organised in the composer's home city of Bradford, re-establishing a connection between them which had ended, as he saw it, with the publication of his memoir.

|

| Norbeck Peters Ford first US edition, 1936 |

A compilation of Eric Fenby's writings about Delius, which included the manuscripts of many lectures and broadcasts, was collated by his friend Stephen Lloyd and published as Fenby on Delius in 1996.

You might also enjoy:

Peel Me A Lotus (1959) by CHARMIAN CLIFT

Christ Stopped at Eboli (1945) by CARLO LEVI

Some Books About… FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN

Last updated 16 October 2021 §

Thursday, 10 December 2020

The Write Advice: CARTOON 013

© 2008 Doug Savage

Thursday, 3 December 2020

The Write Advice 141: ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER

In the process of creating them [ie. his dozens of short stories], I have become aware of the many dangers that lurk behind the writer of fiction. The worst of them are: 1) The idea that the writer must be a sociologist and a politician, adjusting himself to what are called social dialectics. 2) Greed for money and quick recognition. 3) Forced originality –– namely, the illusion that pretentious innovations in style, and playing with artificial symbols can express the basic and ever-changing nature of human relations, or reflect the combinations and complications of heredity and environment. These verbal pitfalls of so-called 'experimental' writing have done damage even to genuine talent; they have destroyed much of modern poetry by making it obscure, esoteric, and charmless. Imagination is one thing, and the distortion of what Spinoza called 'the order of things' is something else entirely. Literature can very well describe the absurd, but it should never become absurd itself.

Although the short story is not in vogue nowadays, I still believe that it constitutes the utmost challenge to the creative writer. Unlike the novel, which can absorb and even forgive lengthy digressions, flashbacks, and loose construction, the short story must aim directly at its climax. It must possess uninterrupted tension and suspense. Also, brevity is its very essence. The short story must have a definite plan; it cannot be what in literary jargon is called 'a slice of life.' The masters of the short story, Chekhov, Maupassant, as well as the sublime scribe of the Joseph story in the Book of Genesis, knew exactly where they were going. One can read them over and over again and never get bored. Fiction in general should never become analytic. As a matter of fact, the writer of fiction should not even try to dabble in psychology and its various 'isms.' Genuine literature informs while it entertains. It manages to be both clear and profound. It has the magical power of merging causality with purpose, doubt with faith, the passions of the flesh with the yearnings of the soul. It is unique and general, national and universal, realistic and mystical. While it tolerates commentary by others, it should never try to explain itself. These obvious truths must be emphasized, because false criticism and pseudo-originality have created a state of literary amnesia in our generation. The zeal for messages has made many writers forget that storytelling is the raison d'être of artistic prose.

Introduction to The Collected Stories (1982)

Use the link below to visit the website of Polish-born North American Yiddish writer ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER (1902–1991):

https://www.bashevissinger.com/

You might also enjoy:

The Write Advice 079: ANTON CHEKHOV

The Write Advice 086: VIRGINIA WOOLF

The Write Advice 098: BORIS PASTERNAK

Thursday, 26 November 2020

Think About It 061: DOROTHY M RICHARDSON

Thursday, 19 November 2020

The Write Advice 140: ANTHONY BURGESS

Fiction is a lying craft and it has no pretensions to exact knowledge. Plausibility is very nearly all. A novelist may check in a cheap encyclopedia such objective data –– details of the sinking of the Titanic, the formula for sodium glutamate –– as he needs for his narrative, but his art is a very tentative one and depends largely on guesswork as to how the human mind operates. As structure is important –– meaning the imposition of a beginning, a middle and an end on the flux of experience –– there has to be a large element of falsification. Nothing could be less scholarly than the average novel, even when its basis is historical fact… The novelist is a confidence trickster, while it is the task of the scholar to abhor trickery and teach scepticism.

'Writer Among Professors' [from Homage To Qwert Yuiop: Selected Journalism 1978-1985]

Thursday, 12 November 2020

Poet of the Month 066: NOËL COWARD

'They were married

And lived happily ever after.'

But before living happily ever after

They drove to Paddington Station

Where, acutely embarrassed, harassed

And harried;

Bruised by excessive jubilation

And suffering from strain

They got into a train

And, having settled themselves in a reserved carriage,

Sought relief, with jokes and nervous laughter,

From the sudden, frightening awareness of their marriage.

Caught in the web their fate had spun

They watched the suburbs sliding by,

Rows of small houses, neatly matched,

Safe, respectable, semi-detached;

Lines of gardens like pale green stripes,

Men in shirtsleeves smoking pipes

Making the most of a watery sun

In a watery English sky.

Then pollard windows and the landscape curving

Between high trees and under low grey bridges

Flowing through busy locks, looping and swerving

Past formal gardens bright with daffodils.

Further away the unpretentious hills

Rising in gentle, misty ridges,

Quiet, insular, and proud

Under their canopies of cloud.

Presently the silence between them broke,

Edward, tremulous in his new tweed suit

And Lavinia, pale beneath her violet toque,

Opened the picnic basket, lovingly packed

By loving hands only this morning –– No!

Those sardine sandwiches were neatly stacked

Lost centuries ago.

The pale, cold chicken, hard-boiled eggs and fruit

The cheese and biscuits and Madeira cake

Were all assembled in another life

Before 'I now pronounce you man and wife'

Had torn two sleepers suddenly awake

From all that hitherto had been a dream

And cruelly hurled

Both of them, shivering, into this sweeping stream

This alien, mutual unfamiliar world.

A little later, fortified by champagne

They sat, relaxed but disinclined to talk

Feeling the changing rhythms of the train

Bearing them onward through West Country towns

Outside in the half light, serene and still,

They saw the fading Somersetshire Downs

And, gleaming on the side of a smooth, long hill

A white horse carved in chalk.

Later still, in a flurry of rain

They arrived at their destination

And with panic gripping their hearts again

They drove from the noisy station

To a bright, impersonal double room

In the best hotel in Ilfracombe.

They opened the window and stared outside

At the outline of a curving bay,

At dark cliffs crouching in the spray

And wet sand bared by the falling tide.

The scudding clouds and the rain-furrowed sea

Mocked at their desperate chastity.

Inside the room the gas globes shed,

Contemptuous of their bridal night,

A hard, implacable yellow light

On a hard, implacable double bed.

The fluted mahogany looking-glass

Reflecting their prison of blazing brass,

Crude, unendurable, unkind.

And then, quite suddenly, with a blind

Instinctive gesture of loving grace,

She lifted her hand and touched his face.

Noël Coward was a creative phenomenon, a man who excelled at every artistic pursuit he turned his hand to including (but not limited to) acting, directing, the writing of more than thirty-five plays, the composition of dozens of songs and their accompanying lyrics, four screenplays, a very good comic novel, many excellent short stories and a great deal of verse. His verse is perhaps the least well known of his accomplishments and that is a pity because it is frequently as good as everything else he wrote, revealing a side of his nature –– as in the example quoted above –– that would appear to be at odds with the popular image of him as an effete, smooth-haired dandy, tossing off cutting quips and memorable bon mots like a latter day Oscar Wilde. There was much more to Coward than the urbane and witty persona he so carefully projected and it is in his verse, and the best of his short stories, that he most often succeeds in the difficult task of touching the reader's heart.

The writing of verse was a necessary daily activity to Coward, a task which afforded him the freedom to step outside his self-maintained boundaries as an artist and experiment. 'I find it quite fascinating to write at random,' he once confided to his diary, 'sometimes in rhyme, sometimes not. I am trying to discipline myself away from too much discipline, by which I mean that my experience and training in lyric writing has made me inclined to stick too closely to a rigid form. It is strange that technical accuracy should occasionally banish magic, but it does. The carefully rhymed verses, which I find very difficult not to do, are, on the whole, less effective and certainly less moving than the free ones. This writing of free verse, which I am enjoying so very much, is wonderful exercise for my mind and for my vocabulary.'

Coward's sense of enjoyment is immediately apparent in a poem like the one quoted above with its precisely chosen images of the English town and countryside and its affecting description of the train journey undertaken by a pair of nervous Edwardian newlyweds to reach their '…bright, impersonal double room / In the best hotel in Ilfracombe.' He makes us feel and share their apprehension and also their genuine but as yet unconsummated love for each other, movingly expressed by the final image of the bride silently reaching up to touch the face of her new husband in front of their '…hard, implacable double bed.' We are invested enough in their story to care what will happen to them and to feel, by the poem's end, that they will conquer their mutual awkwardness and go on to enjoy a satisfying married life together. The poem has the affective power of a short, perfectly constructed film, offering the reader a brief but revealing glimpse of a world in which sex before marriage was a scandalous idea to most middle-class couples like Edward in his stiff tweed suit and Lavinia in her brimless violet hat. Their anxiety feels real to us because it is and remains recognisably human, proving that, while Coward may not have considered himself a poet in the accepted sense of the term, he was perhaps a better one than he gave himself credit for being.

Use the link below to visit the website of British playwright, actor, director, composer, novelist, poet and raconteur extraordinaire NOËL COWARD:

You might also enjoy:

Poet of the Month 056: TS ELIOT

Poet of the Month 052: CARSON McCULLERS

Poet of the Month 039: GEORGE ORWELL

Thursday, 5 November 2020

The Write Advice 139: JOYCE THOMPSON

Interview [15 February 2016]

Thursday, 29 October 2020

Think About It 060: ROLLO MAY

To some extent, it might be said, dictatorships are born and come to power in periods of cultural anxiety; once in power, they live in anxiety –– eg. many of the acts of the dictating group are motivated by its own anxiety; and the dictatorship perpetuates its power by capitalizing upon and engendering anxiety in its own people as well as in its rival nations.

The Meaning of Anxiety [1950, revised 1977]

Use the links below to read a short introduction to the theory and practice of Existential Psychotherapy and watch a 10 minute video that explains the work of North American Existential Psychotherapist ROLLO MAY:

http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/evil-deeds/201101/what-is-existential-psychotherapy

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wms_RXEta5c

You might also enjoy:

Thursday, 22 October 2020

The Write Advice 138: STAN BARSTOW

I was learning, and the first thing I learned was that even with a reasonably fluent flow of words such as I could command, writing insincerely rarely works. Those who write meretriciously have to believe in it while they're doing it. I sold nothing in that first phase. The envelopes came back. But I will not say that I wasted valuable time in trying to write what I thought editors would want, nor in beginning and abandoning two correspondence courses intent on teaching me to please others before I tried to please myself. For, interestingly, the courses I saw never did pretend that they could teach one how to write well, they maintained that they could teach one to make money by writing. With me they did neither, but I soon came to accept them as a necessary part of my initiation and early apprenticeship. They taught me what I didn't want to do and in fact couldn't do. And, while I was disappointed, I didn't despair. Significantly, for the first time when faced with problems and disappointment, I didn't throw my hand in. There had to be some way forward.

In My Own Good Time (2001)

Use the link below to visit The Literature of Stan Barstow, a website celebrating the life and work of British novelist STAN BARSTOW (1928–2011):

http://www.stanbarstow.info/notitle.html

You might also enjoy:

The Write Advice 048: HILARY MANTEL

The Write Advice 038: NICK HORNBY

The Write Advice 005: EDNA O'BRIEN

Wednesday, 14 October 2020

J is for Jazz 014: BING CROSBY

There are virtuoso performers who have not found an identity. That thumbprint is missing. With Bing you knew right away who he was. And you knew that he knew. He really is the first American jazz singer in the white world. Bing was an enormous influence. You couldn't avoid him. He had a good beat. He was a jazz singer, he knew what jazz was, and could sing a lyric, say the words, and make you hear the notes. Bing could swing. When he sang, the tune swung, whatever it was.

Mention the name 'Bing Crosby' to most people and the first image that generally springs to mind is that of an avuncular, pipe-smoking sexagenarian crooning the festive Irving Berlin chestnut White Christmas over a lush if respectfully sedate accompaniment. Even today, more than four decades after his death on a Spanish golf course, Crosby still seems to epitomize the term easy listening –– pleasant, predictable, featuring nothing in his choice of material, arrangements or orchestrations which could conceivably be described as 'cutting edge' or in the least sense challenging.

But this was not always the case for the vocalist, actor, producer, entrepreneur and philanthropist born Harold Lillis Crosby Jr on 3 May 1903 in the Washington port city of Tacoma. There was another Crosby –– he earned the nickname Bingo, later shortened to Bing, from a neighbor thanks to his boyhood fondness for the comic strip Bingo From Bingville –– who, in the words of clarinet virtuoso and bandleader Artie Shaw, '… was the first hip white person born in the United States.' This Bing Crosby was a sonic pioneer, the artist who singlehandedly invented the art of modern popular singing and privately funded the development of the tape recorder, influencing scores of performers both black and white who were as enraptured as the general public so quickly became by his mellifluous baritone voice and relaxed but acutely precise phrasing.

Crosby was first introduced to music by his father Harry Crosby Sr, who brought home an Edison Talking Machine –– the round cylinder-playing precursor to the flat disc playing gramophone –– not long after the family moved from Tacoma to Spokane in 1906. In time this machine was replaced by a Victrola and a collection of 78rpm records featuring the music of Gilbert and Sullivan, Irish tenor John McCormack, Scottish music hall star Harry Lauder and the nation's newest singing sensation, a brash young Jewish vaudevillian named Al Jolson whose 1912 hit The Spaniard That Blighted My Life would go on to sell more than a million copies. Jolson's impact on the young Crosby was immediate and considerable. ' "I'm not an electrifying performer at all",' he would later tell an interviewer. ' "I just sing a few little songs. But this man [Jolson] could really galvanize an audience into a frenzy. He could really tear them apart." ' Crosby knew what he was talking about because he saw his idol perform live in the hit 1917 show Robinson Crusoe Jr while employed for the summer as a prop boy at The Auditorium, the most prestigious vaudeville theater in Spokane. Jolson's repertoire would serve as the template for Crosby's earliest recordings as lead vocalist for The Rhythm Boys, with highly romanticized 'Songs of the Old Southland' (nearly all of which were churned out by professional songwriters in New York City) like Magnolia remaining staples of his own extensive repertoire for the rest of his career.

But Crosby possessed qualities that Jolson, for all his energy and talent, could not realistically hope to equal –– a seemingly instinctual understanding of rhythm and swing, a genuine love of jazz and a gift for understated delivery that demonstrated his mastery of microphone technique at a time when the microphone itself was a new form of technology that could intimidate even the most seasoned performers both in and out of the recording studio.

Crosby's career began in 1923 when he joined a band called the Musicaladers which had been formed by some Spokane high school students, one of whom was Native American pianist/manager Alton Rinker. Crosby was the band's entirely self-taught drummer and occasional featured vocalist and was soon earning enough from its performances at local dances to feel confident enough of his future to drop out of college in his senior year. Despite enjoying a modicum of success in Spokane, the band split up in the spring of 1925, prompting Crosby and Rinker to try their luck as a harmonizing duo, filling in between silent films at the city's newly converted Clemmer Theater –– an experience that would prove invaluable when, still determined to make it big in the music business, they relocated to Los Angeles in the fall.

Luckily, Rinker's older sister was Mildred Bailey –– an already established performer of the 'racy' jazz and blues music popular in the city's speakeasies as illegal gambling and/or drinking clubs were then known. (The Volstead Act, which prohibited the manufacture, sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages within the United States, had passed into law on 28 October 1919, giving the green light to organized crime to make millions by turning drinking into a 'sinful' and therefore desirable activity much favored by the young, including the perpetually thirsty and frequently intoxicated Mr Crosby.) Bailey was impressed by their act and immediately started making calls to try to find them work. She was also the person who introduced Crosby, with whom she would go on to forge a lasting and mutually appreciative friendship, to the recordings of black blues performers Bessie Smith and Ethel Waters and recommended that he listen to a young cornettist named Louis Armstrong who was currently recording for the OKeh label and playing up a storm each night in Chicago. Crosby, who was already a fan of white jazz acts like The Original Dixieland Jazz Band and The Wolverines, took her advice, finding a new source of inspiration in Armstrong's astonishing talent for both instrumental and spontaneous vocal improvisation. This was something he would soon learn to incorporate into his own, much smoother style of singing, using his voice to mimic instruments as he 'scatted' or improvised on melodies like a jazz musician. While it hardly seems earth shattering now, it was a completely new sound in the mid-1920s, paving the way for his successful emergence as a solo artist and influential cultural force throughout the following decade.

But in 1925 all of this still lay ahead of the twenty-two year old crooner from Washington state. His elder brother Everett was also living in Los Angeles at this time and it was he who allegedly got Bing and Rinker their first paying job at the Cafe Lafayette, a speakeasy whose house band was led by Harry Owens (future composer of Sweet Leilani, a faux Hawaiian song that would be a massive hit for you-know-who in 1937). The job didn't last long and, thanks to the persistence of Mildred Bailey, the pair soon auditioned for and were offered a place in a traveling vaudeville revue titled The Syncopation Idea. ('Syncopated music' was one of the early names for jazz, its use in the title of a revue confirming how popular the music had now become among mainstream white audiences.) They toured in this show for thirteen weeks, developing a small but loyal following among college students, and then joined Will Morrissey's Music Hall Revue, earning the same $75 per week they had earned while appearing in their first show. When the Morrissey revue closed, they joined another revue variously known as The Purple and Gold Revue, Bits of Broadway, Russian Revels and, after still more tinkering with its title and running order, Joy Week.

It was while they were appearing in Joy Week at the Metropolitan Theater in Los Angeles that they were handed a note from Paul Whiteman, the most popular bandleader in the country who was billed –– not at all accurately –– as 'the King of Jazz.' Impressed by their mixture of close harmony singing, comedic interludes and occasional use of exotic instruments like the kazoo, Whiteman offered them a featured spot with his band starting at a weekly salary of $150. They made their debut with his organization at the Tivoli Theater in Chicago on 6 December 1926, two months after secretly recording the song I've Got The Girl for their new boss's former saxophonist in a converted warehouse in Los Angeles. It was not an auspicious beginning to what would be Crosby's long and successful career behind the microphone. The song was second-rate at best and somehow recorded at the wrong speed, making him and the higher voiced Rinker sound like a pair of harmonizing chipmunks when it was played at the standard 78rpm speed. Thankfully, their names did not appear on the label of the Columbia release because, as employees of Whiteman, they were contracted to record exclusively for Victor, the same label which claimed exclusive rights to all of the bandleader's recordings.

The Rhythm Boys with Jack Fulton [vocals]

Recorded 23 November 1927

The opportunity to appear with the Whiteman Orchestra was equivalent to winning a million, pre-Depression dollars in showbusiness terms. Not only would Crosby and Rinker be performing nightly with the most popular band in the country, they would also be touring with some of the very best white jazz musicians currently active in North America. These included cornettist Bix Beiderbecke, guitarist Eddie Lang, trombonists Jimmy Dorsey and Jack Teagarden and saxophonists Frank Trumbauer and Tommy Dorsey, nearly all of whom would go on to have significant solo careers in both small group and big band jazz. Appearing in Chicago also allowed Crosby to visit the Sunset Cafe to hear and meet Louis Armstrong, of whom he was later to say, ' "I'm proud to acknowledge my debt to the Reverend Satchelmouth. He is the beginning and the end of music in America. And long may he reign." ' Armstrong returned the compliment in his 1930 recording of I'm Confessin' (That I Love You), consciously mimicking some of his white friend's vocal mannerisms in his own inimitable style. Crosby and Armstrong would go on to perform together many times on both radio and television and would even record a disappointing LP of Dixieland tunes in 1960 titled Bing and Satchmo following their much beloved duet Now You Has Jazz in the film High Society four years earlier.

The Rhythm Boys were an instant hit with audiences and also with Whiteman who negotiated a separate contract for them with Victor and sent them back into the studio in June with some of his best musicians, a group which included Crosby's hotel roommate (and third great musical influence) Bix Beiderbecke, violinist Matty Malneck and saxophonist Jimmy Dorsey. Their first recording featured a co-written Barris original, yet another catchy ode to the genteel 'old plantation' image of the antebellum south titled Mississippi Mud which established the pattern for virtually all their future recordings –– lots of percussive vocal effects, bantering wordplay and, as time progressed, the featuring of Crosby's smooth baritone with Barris and Rinker more often than not relegated to the roles of harmonizing sidemen. This, combined with Crosby's continuing musical education courtesy of Beiderbecke and other musicians attached to the Whiteman organization plus his own growing confidence as a performer, soon saw him being handed regular solo spots by Whiteman's arranger Bill Challis. By April 1928 his name was appearing beneath the bandleader's on record labels and in March 1929 he released his first side under his own name, a soulful number titled My Kinda Love on which he was accompanied only by piano, violin and guitar.

The music business was changing and tastes were changing with it, aided in part by the advent of talking pictures and the enthusiastic reception of early movie musicals like The Broadway Melody and The Hollywood Revue of 1929. The public's fondness for the brashness of Jolson (still modestly billing himself as 'The World's Greatest Entertainer') was replaced by a new craze for crooners like Rudy Vallee, Chick Bullock and Cliff 'Ukulele Ike' Edwards, making Crosby's shift to a full-time solo career a foregone conclusion. Although The Rhythm Boys survived as a group until 1930, it was as a solo artist that Crosby was to find his greatest success and establish himself as the pre-eminent white male vocalist in North America and, in time, throughout much of the Western world. Many of the songs he would record under his own name during the 1930s –– Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams, Just A Gigolo, Sweet and Lovely, How Deep is The Ocean? and I Surrender, Dear to name just a few –– would go on to become well-respected standards, performed not only by vocalists he directly influenced like Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and Perry Como but also by many important jazz artists including Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis and Sonny Rollins.

Crosby's growing presence on the cinema screen –– he had appeared in King of Jazz in 1930 as a member of the Rhythm Boys and would star in a series of comedic shorts for the Educational/Sennett company between 1931 and 1933 –– and on radio in his own nationally syndicated programs brought his music to even an wider audience and, for close to two decades, saw him consistently voted the number one male vocalist in the United States. While his recordings quickly became less directly jazz influenced, featuring elements of Tin Pan Alley, Latin, Hawaiian and Irish music, this didn't prevent him from appearing in the 1941 film Birth of the Blues, a fictionalized account of the early days of jazz, or from recording albums like Bing and The Dixieland Bands, featuring the band of his younger brother Bob Crosby, in 1951 or the outstanding Bing With A Beat featuring Bob Scobey's Frisco Jazz Band six years later. The jazz influence may have become submerged due to commercial considerations and the orchestrations written for him by his longtime arranger John Scott Trotter, but it was always there in his phrasing and in the way he made even the most banal material glide and swing.

For me, Crosby's greatest jazz performance will always be his 1932 recording of St Louis Blues with Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. While it wasn't his first performance with Ellington –– that was a version of Three Little Words he'd cut with the bandleader as a member of The Rhythm Boys in 1930 –– it was certainly his best, proving to anyone who doubts it that he had a feeling for jazz that was, given his race and upbringing, nothing short of remarkable. I've often wondered why he never recorded with Ellington again and what marvels may have been produced had they focused exclusively on interpreting the bandleader's own distinctively evocative compositions. Although Crosby would go on to do many great things before his death in 1977 –– including funding the development of the tape recorder for commercial use and revolutionizing the way radio programs and records were created, marketed and broadcast –– nothing ever quite equalled what he achieved as a young solo star in the third decade of the twentieth century where, as he always insisted, he just happened to be in the right place at the right time.

featuring